As faithfully as we follow recipes and instructions from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the beer we can brew in 2021 will never be same. For one thing, the ingredients no longer exist. In the past several hundred years, farmers and agronomists have selected and cultivated new strains of crops, and we have no way of knowing the exact qualities of the hops, yeast and water that Irish brewers employed. However, with careful reasoning and the help of expert partners, we picked ingredients that had much in common with what was used in Dublin in the 1570s.

Beer’s main ingredient – in the past just like today – is malted barley. In Ireland at this time, the main type of barley used for brewing was known was ‘bere’ (pronounced ‘bear’), a cereal with small grains that grows on a tall stalk that sways and sometimes falls over in the wind. Overtaken in Ireland and elsewhere by more commercial varieties, bere has been preserved in Orkney in Scotland, where it is used for artisanal food production. FoodCult sourced a small quantity from Peter Martin and John Wishart at the Agronomy Institute of the University of the Highlands and Islands. As a landrace crop, isolated from wider agricultural changes, it is a viable option for making this early style of northern European beer.

The sixteenth-century beer called for a significant volume of malted oats – which is now almost unheard of (though a small amount of unmalted oats is commonly mixed in for flavour). Despite efforts to identify landrace strains and grow and malt sufficient heritage varieties, we settled on using one of the few current sources of oats prepared for craft brewing. Both the bere and the oats were malted — steeped in water, allowed to germinate, and then dried, which develops the enzymes necessary for brewing – at Warminster Maltings in Wiltshire, UK. Warminsters use traditional floor malting techniques, a process similar to what was done in the previous centuries.

Malted bere from Orkney

Flaked and malted oats

From the late medieval period, brewers started adding hops to their beers. At this early stage, the varieties of hops used were rarely noted, but there are occasionally hints about their origins. In the Dublin Castle household accounts, the hops are described as ‘Flemish’, which suggests they were imported and possibly arrived directly from the Low Countries. We looked for a heritage variety that derived from Flanders and, with the help of Peter Darby from the UK’s National Hop Collection in Kent, eventually chose a cultivar called ‘Tolhurst’. It shares a number of characteristics with the early Flemish examples.

Tolhurst hops fell out of production in the 1970s, but five plants are still growing in the UK, maintained by the National Hop Collection (see right and below) and hop grower Dorothy Hollamby of A Bushel of Hops. It took three years to produce enough hops for the project. The last batch were harvested just a few days before brewing in September 2021.

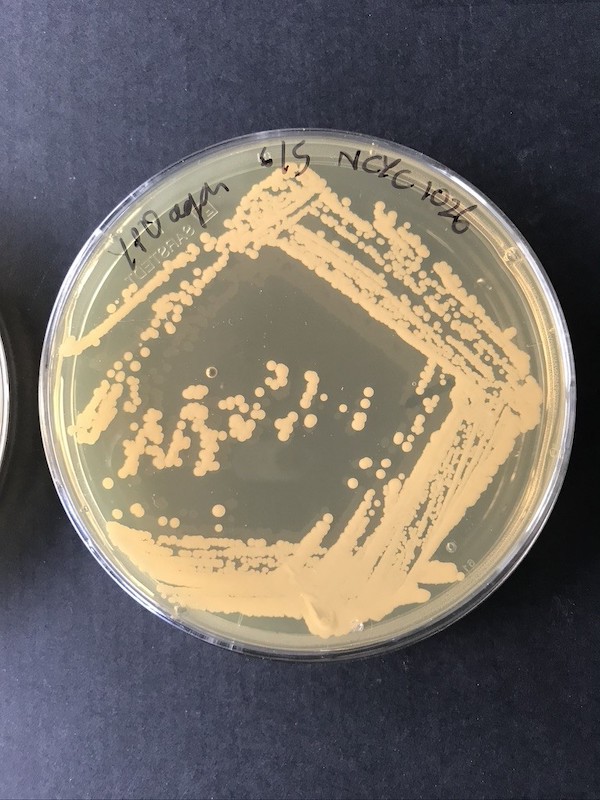

Beer also needs yeast. We cannot know the strains used in sixteenth-century breweries to ferment the ‘wort’, the sweet, malty water boiled with hops. Drawing on the expertise of John Morrissey, a microbiologist at University College Cork, we narrowed down a number of possibilities from the National Collection of Yeast Cultures in Norwich, UK. We finally chose a strain called NCYC 1026. Although the British brewery from which it originated is not revealed, it has the most genetic similarities to the ancestral yeast, known as Beer 1, to which all modern brewing strains can be traced.

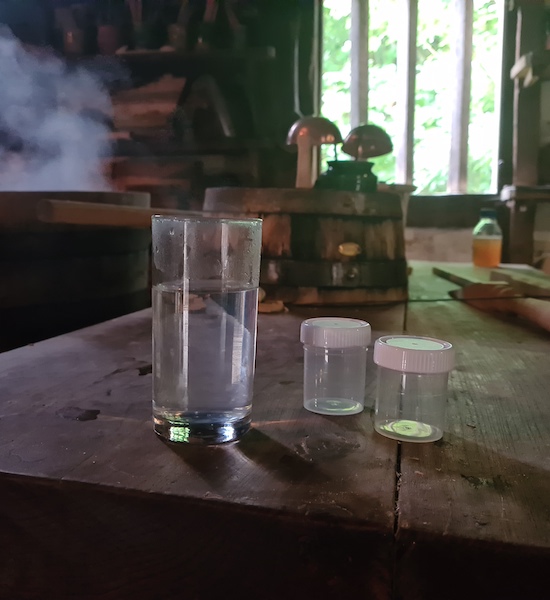

One of the most important ingredients in beer is water. A key reason for choosing the Weald and Downland Museum in Sussex as our brewing location was that the water available was alike in composition to that in Dublin. To ensure that the pH and hardness were comparable, FoodCult archaeologist Ellen O’Carroll (pictured right middle) took samples from part of the surviving medieval watercourse that runs through the Irish capital.