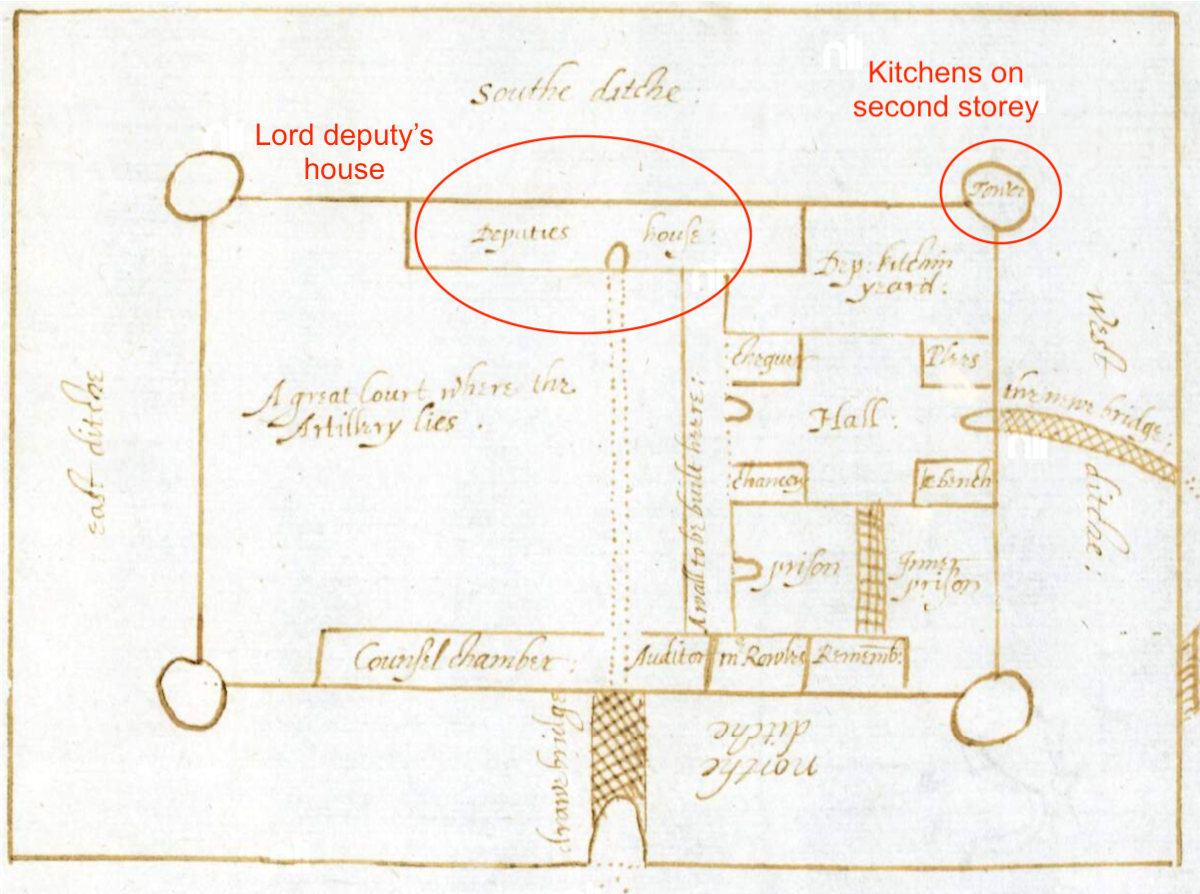

Dublin Castle in the sixteenth century looked very different to the complex off Dame Street today. The so-called Record Tower is the only remnant of the medieval fortress, which was enclosed by thick walls, surrounded by a moat, and entered by an imposing gatehouse to the north. By the Tudor era, the castle had fallen into disrepair. Most viceroys preferred to stay at more comfortable residences elsewhere, like the archbishop of Dublin’s house at St Sepulchre’s or the former monastic estate of Kilmainham.

Above: Lord deputy Henry Sidney departing Dublin Castle, as depicted in John Derricke’s Image of Irelande (1581). Left: The castle as it appears on John Speed’s Map of Dublin from the early seventeenth century, from Trinity College Dublin, TCD MAPS IRL P257.

In his first term as lord deputy (1565–72), Henry Sidney began serious renovations, capped by the erection of one of Ireland’s first public clocks. We know from slightly later plans that the lord’s apartments were tucked inside the south wall and probably housed the main dining room. This is where, according to traveller Henry Brereton, ‘is placed the cloth of estate over my Lord deputy’s head, when he is at meat’. The kitchens were a short walk away, in the second storey of one of the castle’s several towers.

William Fitzwilliam moved into Dublin Castle in the summer of 1572, six months after succeeding Sidney, who happened to be his brother in law. Fitzwilliam was hardly new to Ireland, having served in the country for almost two decades. For most of that time, he had held the positions of vice-treasurer and treasurer-at-war, and stood in for the incumbent lord deputy on multiple occasions.

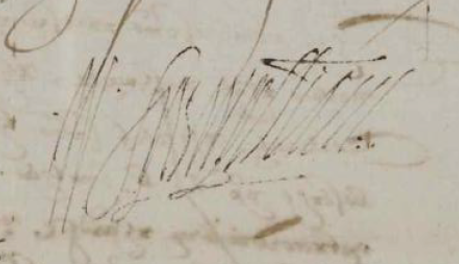

Fitzwilliam’s signature. No portrait of him is known to exist.

Fitzwilliam had not asked for the promotion. In fact, he lobbied Queen Elizabeth and other court grandees to be sent home, citing the high cost of maintaining the English garrisons and representing the monarch abroad. These pleadings were dismissed and Fitzwilliam held the post for three and a half years, before leaving in September 1575. He returned for a second spell in office (1588–94), in which his corruption and heavy handed military interventions fomented tensions with the Gaelic powers that culminated in the bloody Nine Years’ War.

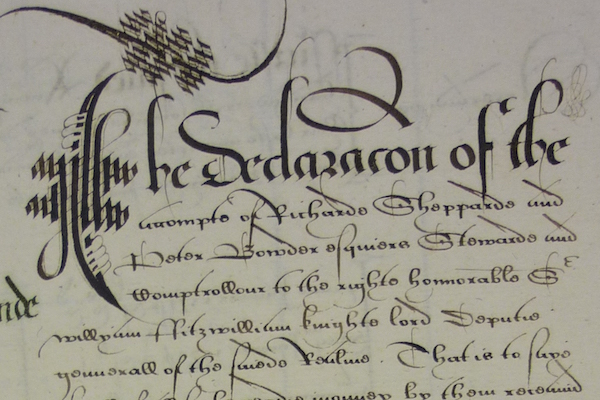

The detailed accounts of Fitzwilliam’s Irish households attest to this financial toll. His chief officers kept meticulous records of purchases, receipts, and expenditure across his two terms. Now held at Northamptonshire Record Office, the accounts are beautifully preserved documents, most of them written in neat handwriting, which may indicate they were produced for a readership, perhaps to prove Fitzwilliam’s trustworthiness and to convey just how much his service in Ireland was costing him personally as well as the public purse.

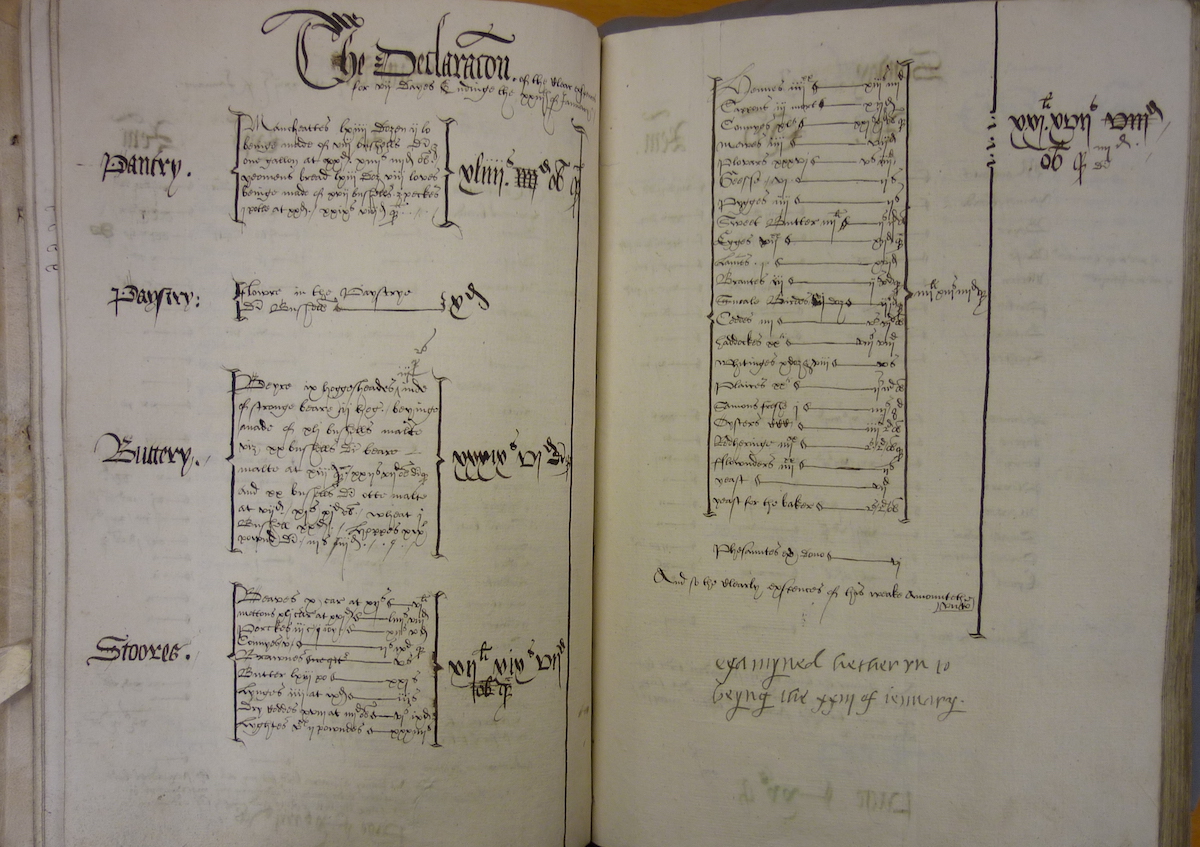

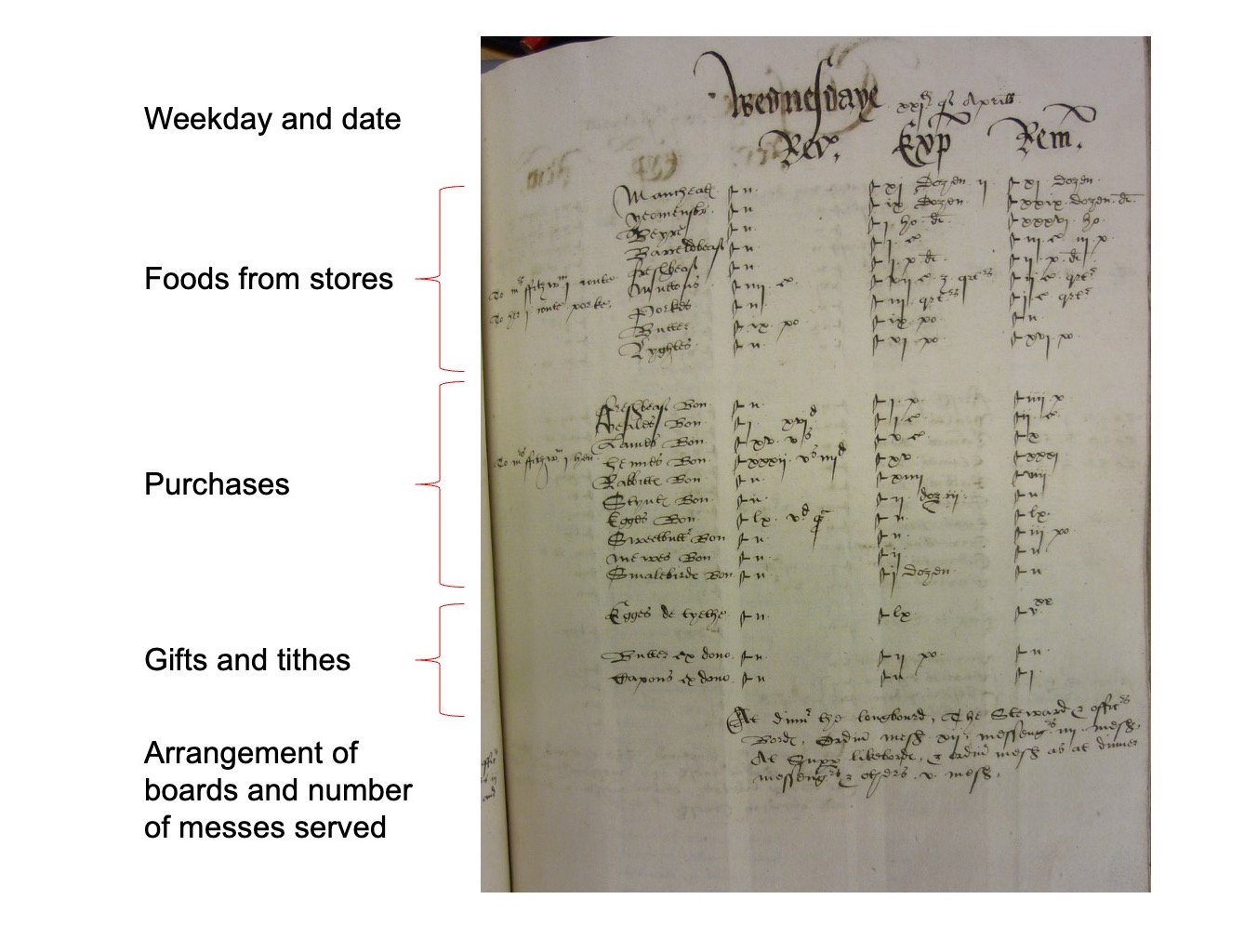

Above: opening page of the full year accounts for 1574, in the names of Fitzwilliam’s steward and comptroller, Richard Sheppard and Peter Bowder. Right: a summary of one week’s expenses from 1574.

The most finely grained are two books from 1574 and 1575, in which a page is given over to a single day, itemizing all the food coming into the kitchens, what was consumed, and what was left. They reveal whether the food came from long-term stores, was purchased from the market, or was received as a gift. We also learn which tables were laid for dinner and supper, the identity of any guests, and the number of staff served at each meal. Other pages, books, and rolls summarize spending by the week, month, and year.

Such sources are well known to early modern historians, but the Fitzwilliam examples stand out. As well as being the best surviving examples from Ireland, they are some of the most detailed accounts that exist for this period in all of Europe. They allow us to reconstruct, in a granular manner, how a huge, aristocractic household, one of the largest in England or Ireland, fed itself.