Across early modern Europe, poultry and wildfowl were mostly enjoyed by society’s upper echelons. Associated in the medieval model of the Great Chain of Being with the element of air, birds were believed by dieticians to be light and delicate foods well suited to the constitutions of noble and other elite diners. This made them perfect foods for feasts and other celebrations involving food.

At Dublin Castle, spending on poultry and game leapt around Christmas, remaining high right through to Epiphany on 6 January. There were no obvious festive fowl—turkey, a large bird that possibly arrived from the New World in the early sixteenth century, was served throughout the year—but the season was marked by a great variety served all at once.

Collectively, the winged offering at Dublin Castle was astounding. There were the wild birds that frequently graced aristocratic tables, like mallards, ducks, teals, sheldrakes, wigeons, quail, woodcock, heath hens, larks, and black birds. Intriguingly, there was a wondrous range of waterfowl, including herons, cranes, gulls, barnacle geese, curlews, redshanks, mewes, snipe, bitterns, godwits, and rails. This is an indication of the rich wildlife in sixteenth-century Ireland, specifically along the coast. A French visitor described seeing ‘flocks on the seashore, and sometimes the air for leagues together darkened by these fowl’. Wealthy English officials like Fitzwilliam were most able to relish the fruits of this landscape.

WILDFOWL CONSUMED AT DUBLIN CASTLE, 1574–5

Bastard curlew — Bittern — Blackbird — Brant — Crane

Curlew — Duck — Godwit — Gull — Heath hen — Heron

Lark — Mallard — Mew — Partridge — Pheasant — Quail

Rail — Redshank — Sea pie — Sea plover — Sheldrake — Small bird

Stint — Stock dove — Teal — Wigeon — Wild goose — Woodcock

DOMESTIC POULTRY

Capon — Chicken

Goose — Green goose

Hen — Pigeon — Plover

Turkey

Domestic birds, like young chickens, older hens, capons, geese, pigeons and plovers, were consumed throughout the year. They may have been purchased live and fattened in the castle’s courtyard, because we know that some of the household’s grain went to feeding poultry. Other birds appeared at different times, perhaps as they were caught by hunters and reached the capital’s markets.

First right: A curlew. Second right: A barnacle goose.

Many of the most prized birds were received as gifts. Among Europe’s elites, exchanging presents, including food, was a powerful ritual, forging social ties across a distance and reinforcing hierarchies between lords of differing ranks and their vassals. We know that gifting remained an important medium of exchange in Gaelic Ireland in the early modern period, but the Fitzwilliam records demonstrate that this culture was vibrant in areas of English influence too.

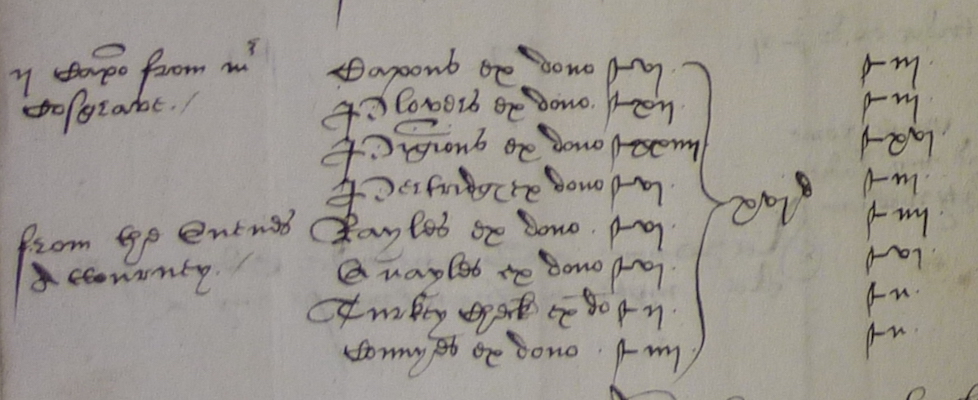

Above: Gifts of capons, plovers, pigeons, partridges, rails, quails, turkeys and conies from the Queen’s Attorney.

In 1574, the lord deputy received 167 food items as gifts, 120 of which were poultry or game. Pigeons were the most common gifts, with partridges, capons, and pheasants coming next. In the household accounts, the sender’s identity was scribbled in the margins. As was typical in England, the majority of presents came from Fitzwilliam’s peers or subordinates. They included the great magnates, like the Earl of Ormond who in October 1574 gave the lord deputy a stag. Other regular senders were Anglo-Irish landowners in the Pale, attempting to curry favour with Fitzwilliam.