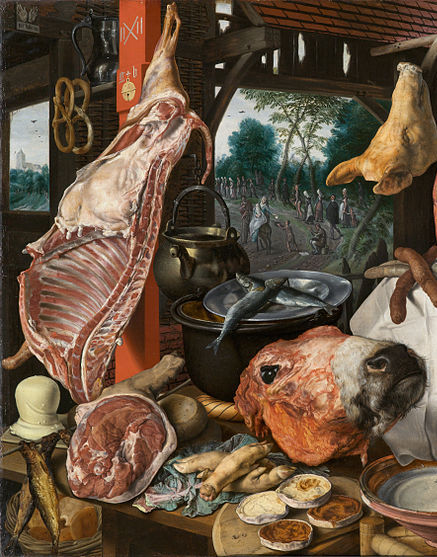

As well as being an essential part of daily nutrition, meat was the one of the most symbolically important foods in this period. At Dublin Castle, the household consumed huge quantities.

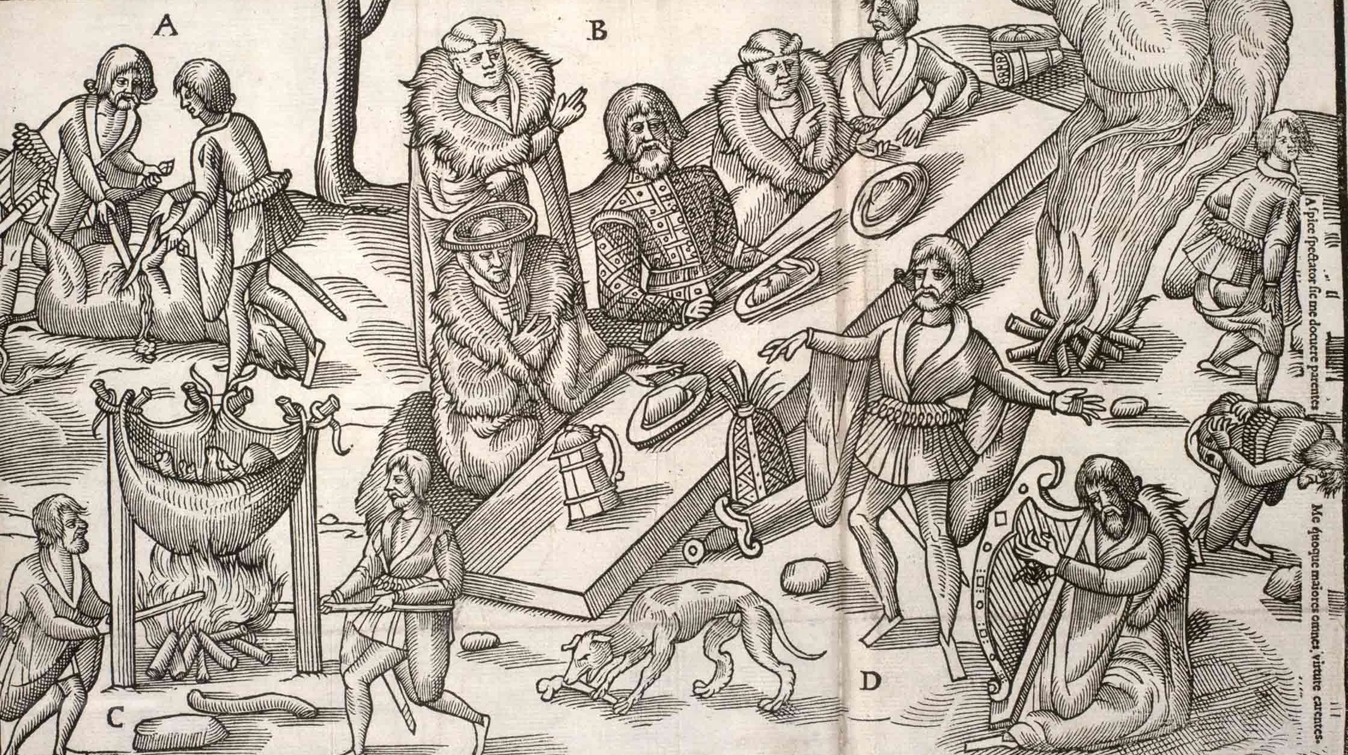

In 1574, meat consumption totalled 267 carcasses of beef and 1,557 of mutton, plus 507 lambs, 85 veal calves, 51 mature pigs and 103 younger ones. Using estimated sizes of animal carcasses, we can work out that each household member could have eaten around three pounds of beef and mutton on average every day. These are high numbers. They tell us, firstly, that meat was integral to certain diets in early modern Ireland. Most historical studies of food on the island have argued in line with late-seventeenth-century statistician William Petty, who wrote that, ‘As for Flesh, they seldom eat it’. Some scholars have suggested that, when the Irish did eat meat, it was at seasonal feasts, as depicted in John Derricke’s Image of Irelande (right).

Different evidence suggests a more complicated picture. Other FoodCult research, including examination of further household accounts, studying animal bone assemblages, and organic residue analysis, indicate Ireland’s population did not just live off the products of animals, like milk. Animals were raised and slaughtered for meat throughout the country.

Secondly, we can focus on precisely the kinds of meat that Castle residents were eating. Beef accounted well over half of the meat consumed by weight in 1574, with mutton accounting for another third. In 1590–1, the proportion of beef was even higher at 69%.

This is interesting because, during this period, the English developed their reputation as beef-eaters. According to dietary writer Thomas Moffett, there was ‘no better meat under the Sun for an English man’. The lord deputy and his entourage were able to express this emerging aspect of their national identity, perhaps more so than they could do at home. But it is also worth noting that beef seems to have been the most important meat across Ireland, in Gaelic areas too.

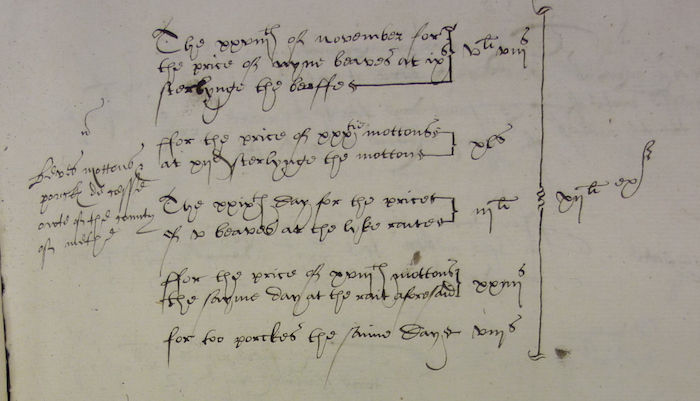

One factor behind the carnivorousness at Dublin Castle was the source of supply. Most of the staple foods consumed by the lord deputy’s household derived from a system known as ‘cess’. Put simply, landowners in the counties around Dublin were obliged to give up a given volume of foodstuffs to the queen’s representative for a fixed price. This was much lower than the market rate, which made the cess hugely unpopular.

Right: Entries for some of the livestock taken for cess in County Meath. Below: An 1805 depiction of a Kerry cow, thought to reflect those in medieval and early modern Ireland. © Trustees of the British Museum.

In one year, 95% of all the cattle killed and eaten at the castle derived from the cess or tithes. Most of the mutton, pork, wheat, malt, and butter came from the same subsidized source. Despite this advantage, Fitzwilliam moaned continually in his letters about the escalating costs of running his house. The high consumption of foods that stood for power and wealth was built on shaky foundations.