Many of the foods regularly at Dublin Castle were exotic. Among these were several types of wine, imported from France, the Rhineland, and the Iberian Peninsula. Short entries in the accounts record the merchants with whom Fitzwilliam’s household officers did business. The kitchens and the cellar also got through vast quantities of sugar. In 1574, the household consumed 672.5 pounds, much of this probably used to sweeten the wine. In this period, the sugar likely originated in the Mediterranean and was still seen very much as a luxury. The lord deputy and his wife occasionally gave parcels of ‘fine sugar’ as gifts, an indication of its restricted supply, even among the elites of Anglo-Irish society.

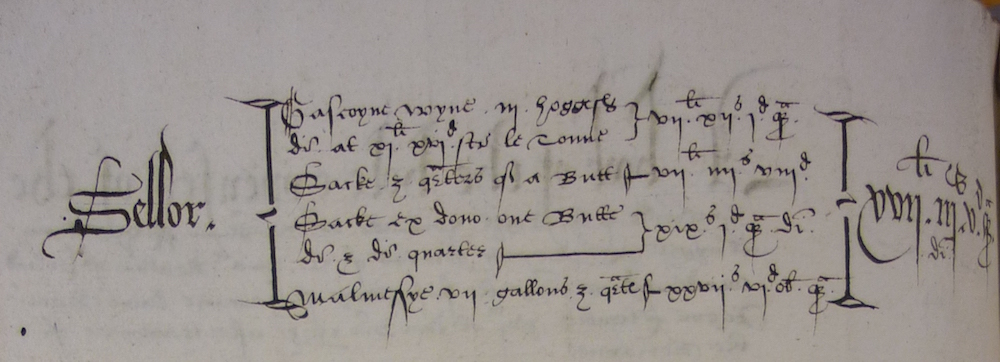

Various wines listed in the Fitzwilliam accounts.

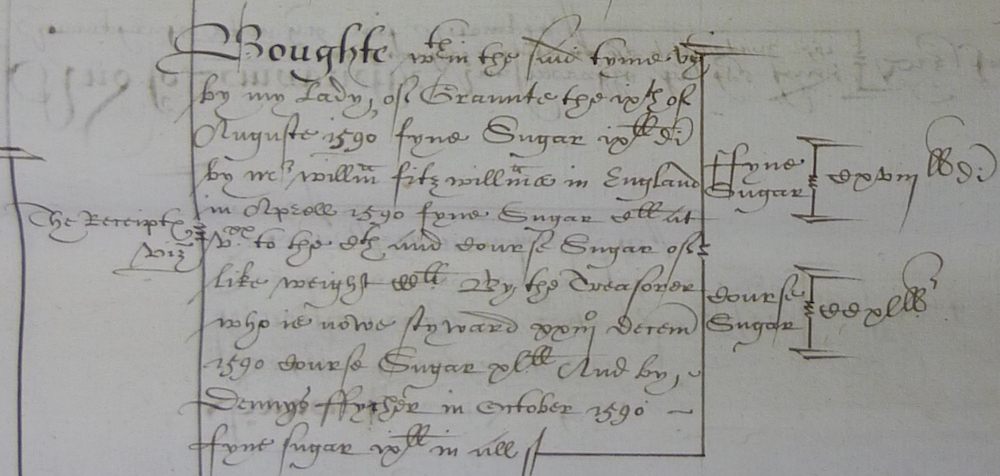

Purchases of sugar during Fitzwilliam’s second term in office.

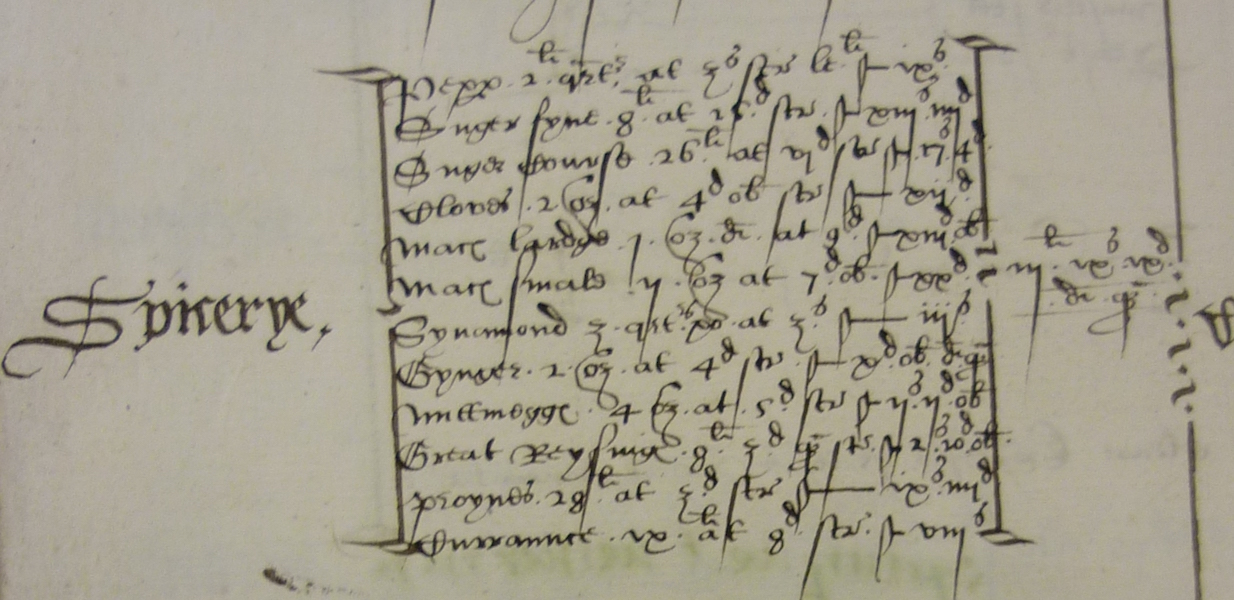

The Fitzwilliams made presents of spices too. The records of spice consumption at the Castle are some of the most intriguing. Because these ingredients must have been shipped in from warmer climes, they are a vivid example of how Ireland was connected to networks of exchange and trends in culinary culture on the continent.

They also offer a tantalising suggestion of how food may have tasted. One of the drawbacks of this form of household account is that it does not reveal how the foodstuffs were prepared and cooked. We only learn what items—manchets, milk, or mackerel—were served on a given day. But knowing how much of each spice was consumed every month, we can track how certain seasons seem to have been associated with certain flavours. Cinnamon, cloves, ginger, mace, nutmeg, and pepper were the most commonly used. Carraway was only employed during Lent. By far, December was the most spice-heavy month. Comparison with other accounts, from Ireland and elsewhere, along with other documents like recipes, would reveal whether these choices were typical of courtly and aristocratic cuisine.

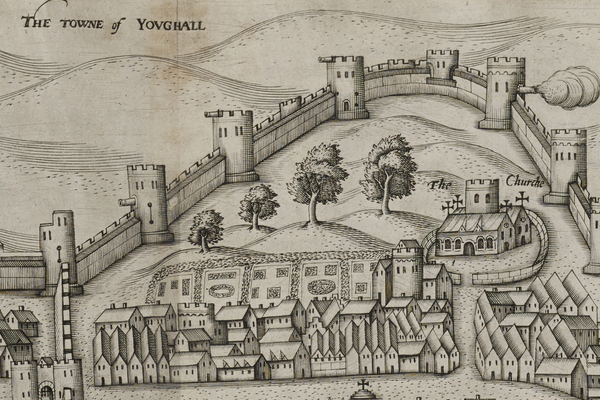

Other fashionable foods that stood out at Dublin Castle were fruit and vegetables. Those mentioned in the accounts are only represent the minimum amount consumed, because the household had its own gardens, the products of which were not recorded coming into the kitchens.

The range of vegetables mentioned in the accounts was striking, certainly for a country not thought to have a strong gardening tradition until later in the seventeenth century. As well as miscellaneous purchases of ‘roots’ and ‘herbs’, Fitzwilliam’s tables were graced with humble vegetables, like parsnips, carrots, turnips, skirrets, onions, leeks, scallions, and cabbages, and delicate morsels like fresh peas, alexander buds, artichokes, lettuce, radishes, samphire, and cucumbers. Some of these were likely dressed with ‘salad oil’, with as much as three gallons expended each a month. There were established orchards throughout the island, so unsurprisingly apples featured often on the menu.

Fruit and vegetables in Dublin Castle accounts, 1571–5

Alexander buds — Apples — Artichokes — Cabbages

Leeks — Lemons — Medlars — Onions — Oranges

Parsnips — Pears — Peas — Plums — Scallions

Skirrets — Tansey — Wardens

Fruit and vegetables in Dublin Castle accounts, 1591–3

Apples — Artichokes — Beans — Bullaces — Cabbages

Carrots — Cherries — Codlings — Cucumbers — Garlic

Green peas — Leeks — Lettuce — Onions — Oranges

Parsley — Parsnips — Radishes — Salad herbs

Samphire — Scallions — Skirrets — Strawberries

Turnips — Walnuts — Wardens

More occasionally, there were pears, plums, cherries, and strawberries, plus oranges and lemons grown in hotter parts of Europe. Formerly, all these foods had a lowly reputation among physicians and dietary writers. But their fortunes were lifted following the Renaissance, as fruit and vegetables, particularly those that took skill to grow, became celebrated among wealthy and sophisticated diners. The rarefied elite at Dublin Castle kept up with these developments, but the taste for plant-based foods may have been spread more widely in Ireland than we might think. Private and commercial gardens existed across the country, especially in towns. In 1609, just a few years after the establishment of Trinity College, the institution’s fellows planted a vegetable plot of their own.