Ireland’s waterways abounded with seafood. For centuries, coastal communities had netted fish and foraged for molluscs and crustaceans for their own consumption. From the late medieval period, fleets from England, France, Spain and other nations sailed in to exploit the productive fisheries off the country’s coasts. Herring was one of Ireland’s most valuable early modern exports, until it was overwhelmed on the European market by Newfoundland cod in the second half of the sixteenth century.

The Fitzwilliam records demonstrate that plenty of fish was eaten locally. The diversity mentioned in household accounts is astonishing. Throughout the seasons, the castle residents ate freshwater species like pike, roach, salmon, and trout, seafish like herring, flounder, whiting, plaice, haddock, cod, gurnard, ray, bass, turbot, and mackerel, and shellfish like crab, lobster, oysters, mussels, and cockles.

FRESH FISH CONSUMED AT DUBLIN CASTLE, 1574

Bass — Bream — Cod — Codlings — Conger

Eels — Flounder — Grayling — Gurnard

Haddock — Halibut — Herring — Hornfish

Knowd — Ling — Mackerel — Mullet — Pike

Plaice — Ray — Roach — Salmon — Shad

Sole — Thornback — Trout — Turbot — Whiting

PRESERVED FISH

Cod — Eels — Herring (red and white)

Ling — Salmon

SHELLFISH

Cockles — Crab — Lobster — Mussels

Oysters — Periwinkles — Razor clams

All of these were purchased fresh from the markets in Dublin, a mark of how these foods were commercially available. They were, however, expensive and from the quantities consumed it is likely that only the higher-ranking members of the lord deputy’s household regularly ate fresh seafood. The majority had a more monotonous piscatorial regime, sticking to the salt cod, ling, herring, and eels bought in bulk from merchants and stored for months.

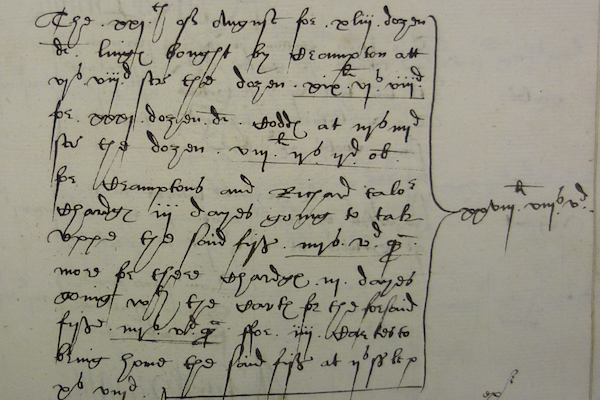

Right: Record of a large purchase of cod and ling, including transport charges.

Compared to the staples like bread, meat, and beer, fish has traditionally received less attention from food historians. But for much of the year it was the centrepiece of mealtimes. Fasting remained a widespread practice in Europe, in both Protestant and Catholic regions, well after the Reformation. Though the precise strictures varied from place to place, most Christians were supposed to abstain from meat on several days each week and at certain other times, including Lent. In 1562, the English Crown introduced an extra weekly fast each Wednesday, claiming that it would support the nation’s fishermen and navy.

Because they record food consumption on a daily basis, the Fitzwilliam accounts allow us to examine how fasting operated on a granular level. By looking at the rise and fall of meat-eating, we find that in 1574 every Friday and Saturday were held as a fast, apart from at Christmas and New Year. Also observed at the castle were the six weeks of Lent, the eves of the feast days of the leading apostles, Purification, Ascension, and the Nativity of Mary. In all, a third of the year was designated as a fast. This did not mean total abstinence. Beef disappeared from the tables, along with most of the veal and pork. A little mutton and lamb were still eaten, though the quantities were sharply reduced. Poultry was unaffected.

Historians know that the third weekly fast day was unpopular and quickly dropped, before it was officially repealed in the 1580s. We also know that small amounts of meat could still be served, perhaps for those were frail or ill. The Dublin Castle accounts provide detailed, concrete evidence of how fasting was followed in practice. The meaning of these practices may also have been shifting. Protestant thinkers stressed that certain foods, like fish, were no holier than others, and encouraged fasting as a moral and spiritual practice, opening up divides with Catholic thinking—but abstention was still a core feature of food culture. At this point, fasting remained central to everyday religious life in the household of the queen’s representative in Ireland.

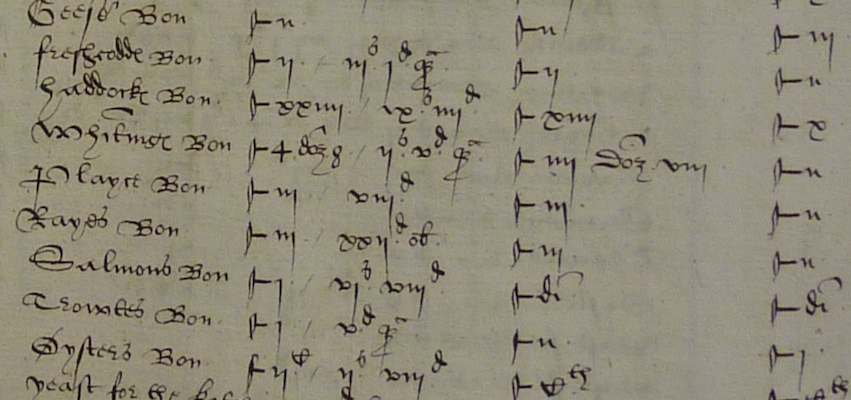

Above: Seafood consumption from a fast day in January 1574. These were the purchases of fresh fish, with preserved cod and ling from the household stores listed further up the page.